When the farms in Missouri’s Bootheel become busy, so do Deb Cook’s clinics.

Cook has been a school nurse in Kennett, Missouri, for more than 30 years. She’s found that when the neighboring corn and soybean fields are cleared with controlled burns or sprayed with pesticides more students come to her with coughs and breathing trouble.

The aerosol particles released throughout the growing season are potent irritants for people with respiratory diseases like asthma.

Asthma is the most common chronic disease and cause of hospitalizations among children. It’s also one of the leading causes of absenteeism in schools. “So obviously it’s going to be of high importance to us, because we want kids in their seat ready to learn,” Cook said.

As the director of health services for Kennett Public Schools, Cook has teamed up with an MU-based program to better equip her school nurses and staff to care for asthmatic students.

Asthma Ready Communities (ARC) provides training and resource support to school districts, clinics, homes and communities across Missouri to improve pediatric asthma care. Based at the MU School of Medicine, the organization runs research initiatives, programmatic interventions and trainings to bring evidence-based care to the public.

ARC founder and director Ben Francisco, PNP, says asthma care goes beyond the clinic.

“There’s a reason that asthma is a public health problem,” he said. “There’s no one entity — a doctor or a school — that can fix the problem. It has multiple dimensions.”

That’s why ARC offers programming in multiple settings, providing professional training for school nurses, clinicians, community health workers and clinic staff. Trainings cover current best practices and teach a common vocabulary to discuss asthma care with patients and parents.

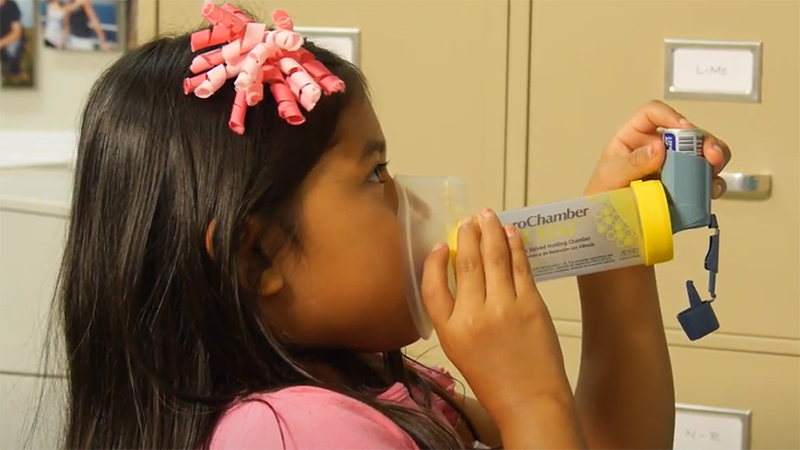

In a school setting, this means equipping nurses to teach proper inhaler technique, assess the severity of students’ asthma and help students adhere to their prescribed treatments.

“We always want to have the conversation… are they supposed to be taking a controller medicine and do they have their controller medicine? Are they taking it regularly?” Cook said. “Those are all questions that we want to talk about over time, and then make sure we communicate with the parent about what needs we see.”

It also means educating teachers and other school staff on the signs and symptoms of asthma and how to reduce environmental triggers in the school building like dust, aerosol cleaning chemicals or scented products.

In clinics, ARC works to get providers up-to-speed on current guidelines, medications and treatment options. Francisco’s team also helps health systems identify needs using Medicaid claims data, which can tell them when patients are being hospitalized for asthma-related complications, whether they’re picking up prescribed medications or over-utilizing antibiotics or steroids.

ARC has run a weekly webinar through Missouri Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) over the past eight years for providers, including school nurses, covering topics such as environmental trigger management, improving inhaler techniques and applying national treatment guidelines. Francisco said the ECHO program has reached more than 1,200 health care workers during the past eight years.

“It’s become a very effective way to not only initiate education for health workforce populations but to sustain their engagement so they’re staying connected, learning more and are aware of updates and changes,” Francisco said.

Today, online educational tools are commonplace in health care. But that wasn’t the case 20 years ago. One of Francisco’s first interventions was a web-based multimedia program called IMPACT Asthma for Kids — a series of animated videos designed to teach children and caregivers how to manage asthma.

A 2003 randomized control trial found IMPACT Asthma for Kids increased knowledge and decreased asthma symptoms, and Missouri public health officials took notice. Soon after, Francisco’s team began partnering with the Department of Health and Senior Services to provide programing to school nurses on asthma treatment.

And as technology has evolved, so has ARC.

One of the biggest challenges to providing quality asthma care in rural settings is access to specialty care. Ideally, asthmatic children receive pulmonary function testing once or twice a year. But in a place like Kennett, where the nearest full-service hospital is 100 miles away, that often does not happen.

ARC’s next project “At Last, Asthma Care at Home” (ALPACAH), aims to bring those services not only to areas in need, but into patients’ homes. ALPACAH will provide families of children with poorly controlled asthma with portable devices that measure lung function — something that could previously only be done in specialized care settings.

“I kind of think of it as a capstone project,” he said. “We’ve been at this for 20 years. We’ve faced a lot of challenges, and we’ve had great support from foundations and the CDC, but some of the core problems have never been solved. This ALPACAH project offers an opportunity to really overcome some of the last barriers to having really good asthma care.”