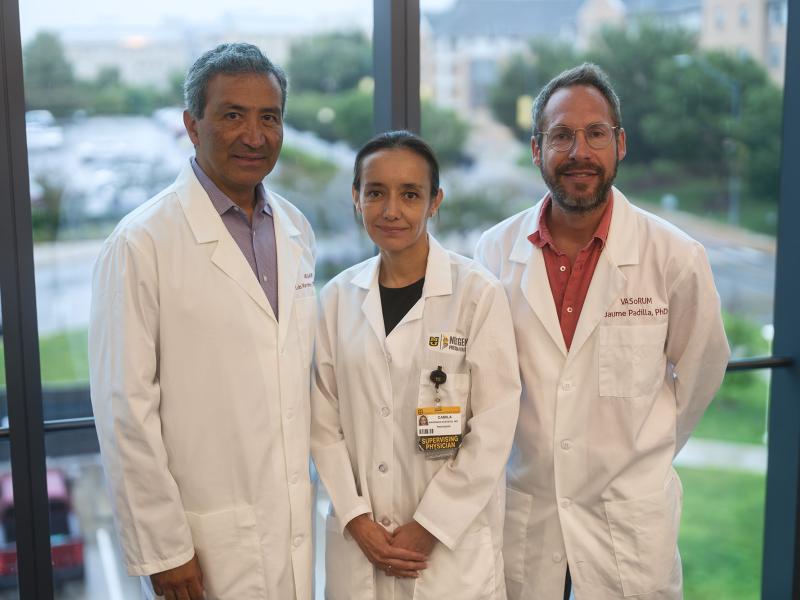

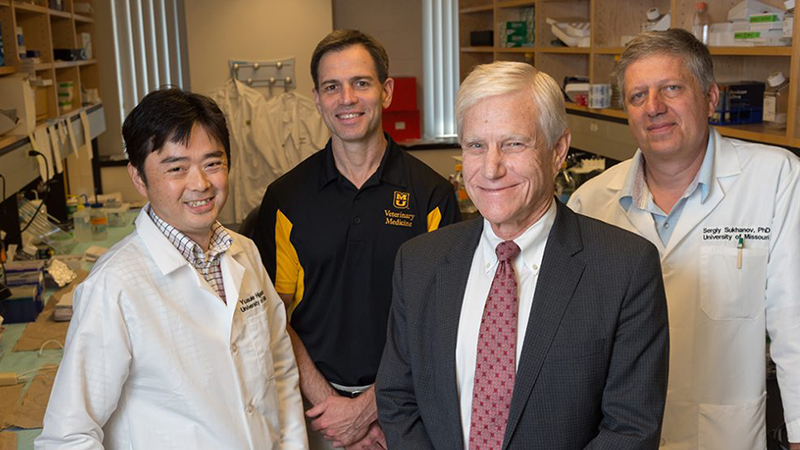

College Avenue separates Patrick Delafontaine, MD, and Doug Bowles, PhD, but a mutual interest in unclogging arteries brought the two together. The dean of the University of Missouri School of Medicine and the chair of the College of Veterinary Medicine’s Department of Biomedical Sciences are collaborating on research that could help prevent heart attacks.

For the last 15 years, Delafontaine and his team have conducted National Institutes of Health-funded research on atherosclerosis — plaque buildup in arteries. Specifically, Delafontaine has studied the effectiveness of the protein Insulin Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1) in reducing plaque in the arteries of mice.

“We have had some breakthroughs recently that indicate this protein might be quite effective at reducing blockages and preventing heart attacks,” Delafontaine said. “We wrote a proposal to the National Institutes of Health to take this to the next level, which is to do a large animal study before taking it to humans.”

That’s where Bowles came in. He, too, has researched atherosclerosis for decades. And he had access to the perfect pig models. That made the proposal more attractive to the NIH, which awarded a R01 Grant in July that is worth $2.4 million over four years.

The pigs in question are genetically disposed to high cholesterol and will be fed a high-fat diet to accelerate disease development. They will be treated with IGF-1 to determine if it limits plaque buildup.

This project also studies the role of LARP6, a mRNA-binding protein that Delafontaine and his colleagues have shown helps induce collagen synthesis and plaque stabilization in animals with atherosclerosis.

“What kills people in heart attacks are the acute myocardial infarctions that have no symptoms beforehand, no warning,” Bowles said. “All the sudden, you have a heart attack and you die. That’s because you have these relatively small lesions that don’t induce any symptoms, but they rupture, form a big blood clot, and that blood clot blocks the flow of blood to the heart and causes the fatal heart attack.

“This IGF that Patrick and I are looking at, we’re trying to stabilize those plaques so those small plaques don’t rupture. If nothing else, progress to bigger plaques that at least give you some symptoms that we can treat through medicine or through stents, but take away the sudden fatal heart attack.”

IGF-1 is approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat children with growth disorders. The supply is limited and expensive. The amount required to treat pigs whose weights approach 200 pounds would cost millions of dollars, Delafontaine said. Fortunately for the researchers, the pharmaceutical company Ipsen donated IGF-1 for the project.

“We’ve got to thank the NIH for their support, but we’ve also got to thank the company that provided us this medication,” Delafontaine said.

The study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (R01HL070241).