Before college, Luke Stephens, MD ’08, had never lived in a town of more than 600 people. His interests still reflect his rural upbringing in Stoutland, Missouri. He enjoys hunting, fishing and tinkering with the modified stock car he occasionally races on dirt and asphalt tracks.

That background can come in handy when Stephens sees patients at MU Health Care’s family medicine clinic in Ashland.

“When I’m talking to patients and trying to explain what’s going on with their blood pressure, I can compare it to the hydraulics in their tractor,” Stephens said. “Having that background helps quite a bit with patients to help them understand. When patients understand, they do so much better.”

Stephens warmed to the idea of practicing in a small town while he was a student at the MU School of Medicine participating in the Rural Scholars Program. Even after getting a taste of city life while completing a sports medicine fellowship in Chicago, he eagerly agreed to come back to mid-Missouri to lead the Ashland clinic when it opened in 2017. He was there for the clinic’s ribbon-cutting — “first time I ever got to use the gigantic novelty shears” — and has tried to build a connection with the town’s people. He even volunteers as the team doctor for the Southern Boone High School football team.

“I have a strong desire to work with people from a rural background,” Stephens said. “My practice mostly is that.”

That bond between a doctor and community is important but increasingly rare in small towns across Missouri. While 37% of Missourians live in rural communities, only 18% of Missouri physicians practice there. As the Baby Boom generation ages and needs more care, the crisis will worsen in rural Missouri, where a greater percentage of the population is over the age of 65.

The MU School of Medicine took one step to address the physician shortage with its class expansion project, which included the founding of the Springfield Clinical Campus in 2016. That allowed MU to increase its class sizes from 96 to as many as 128.

Another key initiative is the Rural Scholars Program, which is designed to find and train students to practice medicine in small towns. It recruits students from rural areas through the Bryant Scholars Pre-Admissions Program and gives students clinical experience in rural health care settings during medical school.

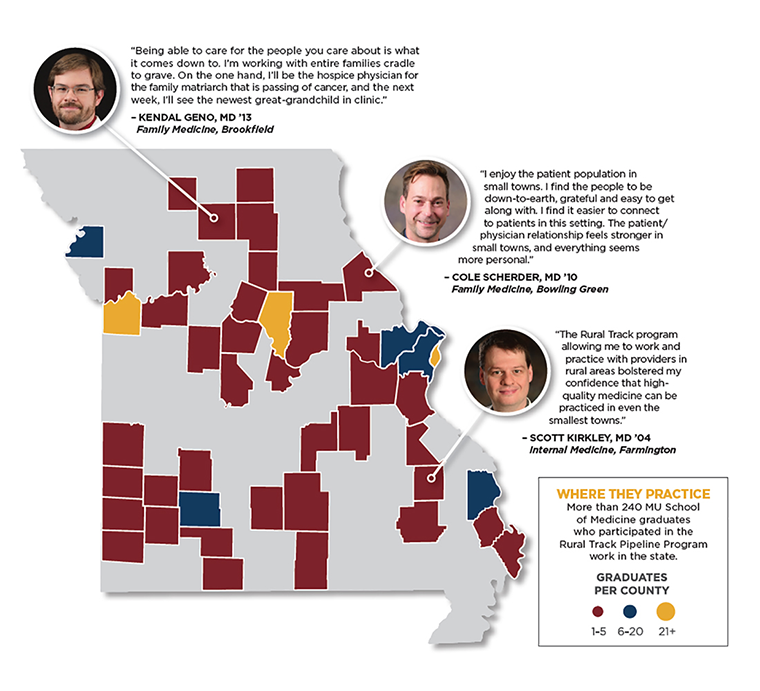

Where They Practice

The rural scholars program, which began 25 years ago, received a boost in September when the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) awarded two grants totaling almost $5 million to the MU School of Medicine. The money will be used to expand the Rural Scholars Program and to fund a new family medicine residency at Bothwell Regional Health Center in Sedalia.

Kathleen Quinn, PhD, former associate dean for rural health, said the larger of the two grants — $4.2 million over four years — will support three goals.

- Develop and implement new curricula to teach the broad skills needed for primary care and rural practice.

- Develop and implement interprofessional curricula in which medical students can learn about rural team-based care alongside pharmacy, nursing and health professions students.

- Increase the capacity of faculty who train medical students to practice medicine in a rural setting.

“Because we’ve had the Rural Scholars Program for so many years, this grant is really about enhancing and expanding our efforts,” Quinn said.

The second grant, worth $750,000, directly addresses one contributing factor to the state’s physician shortage — not enough residency slots. As of 2018, Missouri had 725 residency slots for about 1,000 graduates of the state’s medical schools. The grant will fund the development of a new MU family medicine residency. Two medical school graduates will be selected each year for the residency. They will spend their first year training in Columbia and the next two years in Sedalia.

“Residents are most likely to practice in the state where they do their training,” said Erika Ringdahl, MD, director of the MU School of Medicine’s family medicine residency program. “Right now, we have fewer residency slots than medical students graduating in Missouri, so we’re exporting medical students to other states and potentially losing them. By increasing the number of residency slots, especially in primary care, we hope to retain those physicians who trained in our state and hopefully get them into areas of the most need.”

Stephens is an example of both the Rural Scholars Program's effectiveness and the importance of keeping graduates close to home for residency. He was pre-admitted to the School of Medicine as a Bryant Scholar. He decided he wanted to practice primary care in a rural setting after spending a summer getting clinical experience with Barton Warren, MD, in Richland, Missouri. Stephens completed his family medicine residency at MU and took his first job as a physician at MU Health Care’s family medicine clinic in Fulton. Even after his fellowship in Chicago, he felt the pull of Missouri.

Stephens said he would like to buy 20 or 30 acres of farm land and enjoy country living with his wife, Amanda Stephens, MD ’10, an OB/GYN at MU Health Care, and their children. Many of his patients, who hail mostly from Ashland and nearby small towns such as Hartsburg and Holts Summit, can relate to that sentiment.

“There’s that natural skepticism when patients come in, but once you start talking about your similar backgrounds, I think I bond pretty well with the road construction workers and equipment operators,” Stephens said. “They see me for more than just the white coat or the stethoscope.

“When I have those interactions, I really start to develop a relationship. That’s when I start to learn more about them, and they open up to me and I can get to the root of it. A lot of it is not just what’s going on medically but what’s going on in their lives. That’s when medicine is really powerful.”