By Eric Stann

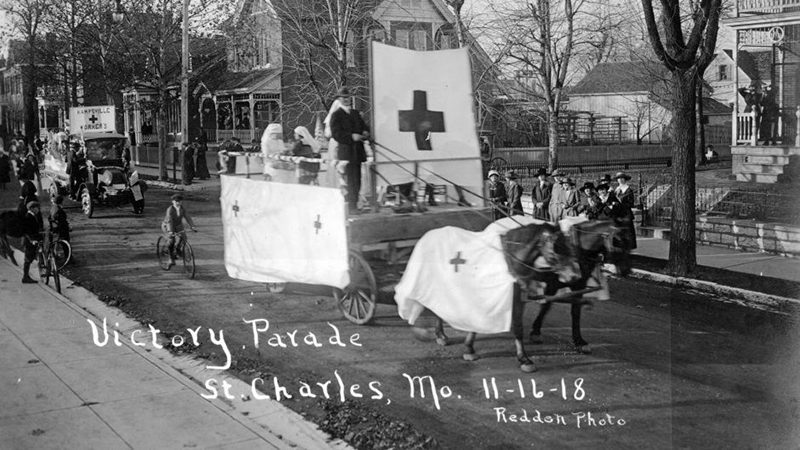

What can the 1918 flu pandemic teach us about the current COVID-19 pandemic? That’s what a group of researchers at the University of Missouri led by Drs. Lisa Sattenspiel and Carolyn Orbann hope to uncover with the help of a recent COVID-19 RAPID grant from the National Science Foundation.

The one-year grant allows researchers to study the 1918 flu pandemic in Missouri. Their findings could help inform strategies for mitigating the spread of the current virus in the U.S.

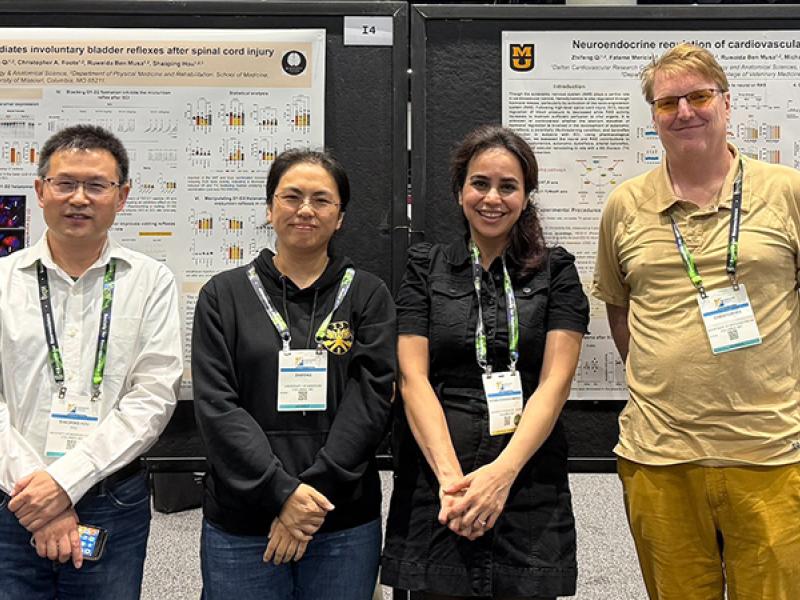

Researchers from MU’s Christopher S. Bond Life Sciences Center, College of Arts and Science, College of Engineering, College of Veterinary Medicine, School of Health Professions and School of Medicine are involved in the project. Xiu-Feng “Henry” Wan, PhD, a professor of molecular microbiology and immunology, electrical engineering & computer science, and veterinary pathobiology, brought the researchers together before COVID-19 last fall to conduct research across disciplines on the nature of viruses and vaccines.

“With any science today, you need a much more interdisciplinary approach,” he said. “You need to understand a subject from a different point of view.”

Jane McElroy, PhD, professor of family and community medicine, focused on rural Missouri counties’ ability to control the COVID-19 pandemic based on their health system features and capacity.

“The subsequent waves of the 1918 influenza hit harder in rural areas, which had been unexpected,” McElroy said. “Life was a bit different back then, but there are still many similarities today, especially in rural places. We want to find out if there are particular characteristics in rural communities that are parallel to the spread of the 1918 influenza for the chance to intervene and possibly save lives.”

Lisa Sattenspiel, PhD, chair of the Department of Anthropology in the College of Arts and Science, and Carolyn Orbann, PhD, an associate professor of health science in the School of Health Professions, are the co-principal investigators on the project.

“Any kind of infectious disease in humans is a really complex problem,” Sattenspiel said. “If you want to fully understand a disease’s impact, you not only have to understand the biology and epidemiology of the disease, but you also have to understand the social circumstances — how people are interacting, spreading and responding to the disease and why people are doing what they do. That’s what we will be able to do here with all of the various disciplines involved with this project.”

The project will use Missouri death certificate data between 1918-1920 from people who died from influenza and pneumonia, because it was difficult at the time to distinguish which respiratory disease was the actual cause of death. The team will develop a detailed analysis of the 1918 pandemic, including geographical spread, underlying socioeconomic conditions and any differences between rural and urban areas in the state. The researchers said their analysis will also include racial and ethnic disparities but will be limited because of the amount of information that is available from that time.

Orbann said by studying a three-year period and not just 1918, the project also could provide valuable information about the potential for additional outbreaks — called an echo wave — beyond the first geographical spread of the disease.

“Existing research on the 1918 pandemic has shown that some places around the world experienced what looks like an echo wave all the way to 1920,” Orbann said. “For instance, some places in Missouri reported more deaths in late 1919 and early 1920 than during the peak in 1918. That information could help us better understand if places that escape the first wave of coronavirus — where we are now — could have the potential to get hit hard with the virus later on.”

This story originally appeared in Mizzou News on June 9, 2020.