Volume of mechanical thrombectomies at hospitals does not correlate with improved stroke outcomes

According to new research from the University of Missouri School of Medicine, the number of mechanical thrombectomies performed at hospitals is not an accurate indicator of patient outcomes.

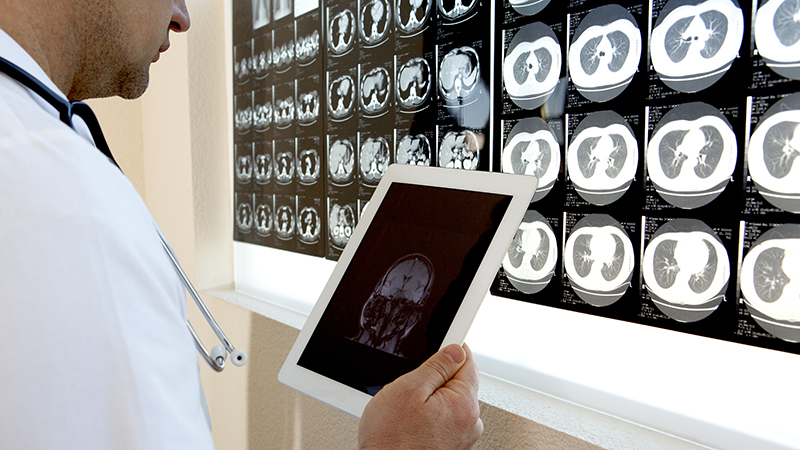

A mechanical thrombectomy (MT) is a procedure that removes blood clots from the artery or vein and is often used to treat ischemic strokes, where the clot blocks blood flow to the brain. Using data from nearly 1,000 hospitals, researchers found that patients undergoing MTs at smaller, rural hospitals did not have less favorable outcomes than patients at large health care systems.

For stroke survivors, a good or favorable outcome means they have high functional independence, which refers to their ability to complete everyday tasks without assistance.

These small hospitals conduct less than 15 MT procedures per year, which is less than what is required for certain stroke center certifications. Considering this new data, study author Dr. Adnan Qureshi said it’s important to reevaluate the relationship between the number of procedures and patient outcomes.

“There is an increasing recognition that a large number of patients who could benefit from a thrombectomy are not receiving it,” Qureshi said. “Increasing the role of smaller hospitals and centers may be the key to increasing availability.”

By expanding access, stroke victims who live hours away from comprehensive stroke care can still receive an MT at their local hospital, and any other care they need.

“One way we could increase the role of smaller hospitals is to provide traveling physicians who know how to perform a thrombectomy,” Qureshi said. “Other ways include updating their infrastructure and resources.”

Researchers also found that larger hospitals with a higher volume of MT procedures saw more adverse outcomes — like death or permanent disability — in stroke patients than smaller hospitals.

“There are several potential explanations for this,” Qureshi said. “Hospitals that perform more thrombectomies also tend to see patients with a higher stroke severity, or those who are at higher risk because of another illness or condition. Smaller hospitals may not have the resources to treat these patients.”

Qureshi said this also may be because larger hospitals are more likely to see more complex patients, so the chance of adverse outcomes or permanent disability occurring is higher. Still, the data suggests the number of MT procedures is not an accurate indicator of quality of care, and other factors such as illness severity should be considered in certification processes.

Dr. Adnan Qureshi is a neurologist at MU Health Care and a professor of neurology at the MU School of Medicine. He is also the program director of the Endovascular Surgical Neuroradiology Fellowship.

“High mechanical thrombectomy procedural volume is not a reliable predictor of improved thrombectomy outcomes in patients with acute ischemic stroke in the United States” was recently published in Interventional Neuroradiology. In addition to Qureshi, MU study authors include Dr. Camilo Gomez, professor of neurology and Dr. Farhan Siddiq, associate professor of neurological surgery. Co-authors Hamza Maqsood, Daniel Ford, Daniel Hanley, Ameer Hassan, Chun Shing Kwok, Thanh Nguyen, Alejandro Spiotta and Syed Zaidi also contributed.