Courtney Perrett, cperrett@missouri.edu

In 1974, 15-year-old Becky Lou Zentz was diagnosed with aplastic anemia, a bone marrow failure syndrome that meant her body couldn’t make new blood cells, leading to anemia and extreme immunodeficiency. From Colorado Springs, Colorado, she traveled to the University of Missouri Children's Hospital for treatment, even though the odds were stacked against her.

At Mizzou, Zentz volunteered for research that helped pave the way for monumental advances in blood transfusions, the development of immunosuppressant drugs and bone marrow transplants. Although Zentz died from her condition a day after celebrating her 16th birthday, her family said she was proud of contributing to medical research that was poised to save lives like hers.

To honor the 50th anniversary of their sister’s passing, the Zentz family recently visited the new MU Health Care Children’s Hospital — calling it the perfect place to remember Zentz’s legacy and her fighting spirit.

History in the making

In the 1970s, the survival rate for patients with bone marrow disorders like Zentz’s was less than 20%. Some 50 years later, that survival rate is now more than 90%, thanks to contributions by Becky and scores of others who participated in cancer research.

In 1974 Zentz was first diagnosed with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, a rare blood condition that can be fatal. Later, doctors realized she had overlapping aplastic anemia — making her one of the youngest patients to be diagnosed with it at the time.

“Aplastic anemia occurs when the blood cells created in the body’s bone marrow are low,” said Tyler Severance, a pediatric hematology/oncology doctor with Mizzou’s School of Medicine. “The three cell types typically affected — which are responsible for carrying oxygen, fighting infection and stopping bleeding — are critical for survival.”

But Zentz wasn’t producing them, which made her body extremely vulnerable.

In the past, doctors tried to treat these conditions with immunosuppressant drugs in an attempt to reset the patient’s immune system. At the time, blood transfusions and bone marrow transplants were in their infancy as potential therapeutics.

“Now we give transfusions frequently,” Severance said. “They’re much safer and better tolerated by patients. There have been advancements across the fields of medicine, in part due to heroic patients like Becky, but also because hospital systems and medical communities have come together to collaborate. I love our blood bank because the people there move heaven and earth to make sure transfusions are safe and as high quality and efficient as possible.”

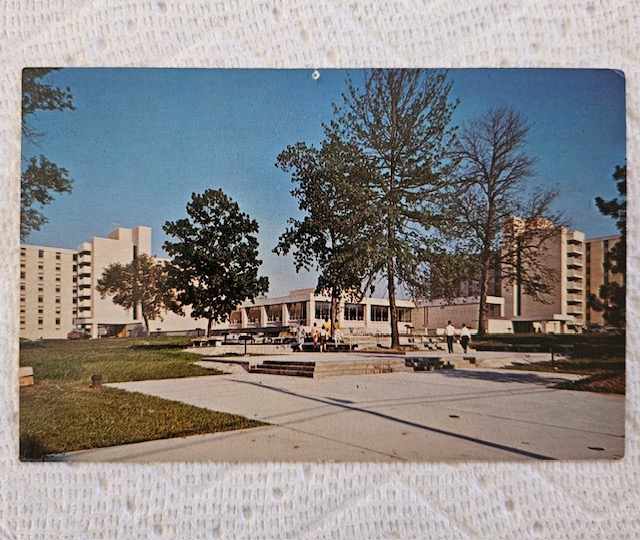

Back in Colorado, Zentz and her family struggled to find adequate treatment to improve her prognosis, which led them to seek out a clinical trial at the Children’s Hospital at University Hospital on Mizzou’s campus.

“Ultimately, there weren't a lot of great options for Becky at the time,” Severance said. “And there was such a strong emphasis in the medical community to learn and figure out what's happening that these patients would travel to the nearest locations that offered clinical trials because that was oftentimes the only realistic pathway to cure.”

The clinical trials held in the 1970s led to an explosion of medical research and advancement, including the implementation of Cyclosporine — a pioneering immunosuppressant drug widely used today to treat conditions like aplastic anemia.

“Becky and patients like her represent a modern miracle in medicine that was 50 years in the making,” Severance said. “At Mizzou, we're fortunate to offer the latest and best treatment pathways because of the heroic efforts of the patients, clinicians and the medical community that came before us.”

A brighter future for all

When her illness progressed, all Becky wanted to do was make it to her 16th birthday, her sister, Mellany Mercer, recalled.

“When she was little, Becky was a huge tomboy,” Mercer said. “She loved to climb, and she’d get up onto the roof of our childhood home and just hang out up there. Even though she didn’t have long with us, she lived a lot of life.”

During the weeks Zentz and her parents were in Columbia for treatment, her siblings came to visit and made themselves at home in the pediatric wing of Children’s Hospital. In the dynamic and welcoming halls of the brand-new Children's Hospital a half-century later, the Zentz siblings fondly remembered their last moments with their beloved sister.

“Fifty years is such a significant anniversary that I wanted to get our siblings together to celebrate Becky,” said Steve Zentz, Becky’s older brother. “Our family was originally from Kirksville, Missouri, and Becky spent a lot of time at the former Children’s Hospital, so it seemed like returning to celebrate the new hospital was the right place to get together.”

Complete with personalized consultation rooms, specialized play areas for different age groups of children, a soundproof room for difficult conversations and rooms for families to stay, the new hospital represents the latest leading-edge facility on Mizzou’s campus designed to support Missourians and communities beyond.

“We’ve brought together all our highly specialized teams, top researchers and advanced resources in one location to ensure our patients receive the best possible care close to home,” said Richard J. Barohn, executive vice chancellor for health affairs and dean of the School of Medicine. “The new Children’s Hospital is an amazing resource that will serve people like Becky and her family for generations to come.”

As one of the nation’s leading research universities with world-class resources, Mizzou is poised to take the knowledge of the past half-century and use it as a bedrock of discovery for the next one.

This story originally appeared on ShowMeMizzou.com