Dr. Jennifer Allen has far too often seen how the devastating effects of opioid addiction can take a toll on a community. Whether it’s in her primary practice in Quincy, Illinois, or her Friday clinic 30 minutes away in Hannibal, Missouri, patterns tend to emerge when it comes to opioids.

“I’ve seen it breaking up families,” Allen said. “A lot of people have said to me, ‘I’ve lost my family. I’ve lost my wife, my children because of my drug problem. My wife left me and said she wasn’t going to put up with this. I need help.’ ”

The reality of working as just one of a handful of physicians in small towns dealing with so much addiction can be overwhelming. Comparing treatment notes in relatively isolated areas simply isn’t an option for Allen as it might be for a doctor in a large, metropolitan area.

Thankfully for Allen, the University of Missouri School of Medicine has recognized the problem and is doing something about it.

Show-Me ECHO — which stands for Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes — is a program of the University of Missouri School of Medicine that allows specialists to train primary care physicians statewide to identify and treat chronic conditions using videoconferencing. An Opioid Use Disorder Show-Me ECHO — which began on Sept. 8 — provides participants with opioid treatment techniques and best practices from medical, pharmacological and psychological professionals.

“In the world of addiction medicine, there are a lot of us who are out here by ourselves,” said Dr. Joseph Toney, a family medicine doctor in Piedmont, Missouri, a town of about 2,000 in Southeast Missouri. “It is nice to have a community and feel like you are not out there in the wind. … If you have one or two people that can answer your phone calls, it is just nice to get a variety of perspectives. That’s what I am trying to gain from the ECHO.”

“Sometimes I feel like I’m in Alaska, four hours from town, even though I’m in Hannibal,” Allen said of the Northeast Missouri town, population 17,000. “Yes, there are other docs here, but if you don’t know each other, it’s harder to reach out.”

Dr. Doug Burgess, the medical director of outpatient psychiatry at Truman Medical Centers and an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, is playing the role of “facilitator” for the Opioid Use Disorder ECHO program. It’s Burgess’ role to connect these medical professionals from all corners of Missouri and facilitate interactive sessions that connect teachers (specialized experts in treatment) with students (doctors who have not had access to such training). Burgess notes that these experts “tend to be in larger cities,” making the ECHO program that much more crucial for doctors such as Allen and Toney.

“What we want to do is take people across the state who are currently treating people with opioid use disorder but feel like they haven’t had the training, or they don’t have the support they need to provide the best care for all their patients,” Burgess said. “This serves as a resource for them to learn and also have access to expert consultants even if they’re located in very rural areas. It also offers them the opportunity to continue medical education. Our ultimate goal is, we want to expand access to effective treatments for opioid use disorder. If clinicians feel more supported, if they feel like they have the knowledge base to effectively treat people with opioid use disorder, my hope is that they are more likely to offer these treatments and more people have access to them.”

Allen graduated from the University of Missouri School of Medicine in 1994, long before the opioid crisis gripped the nation. But eventually, she couldn’t help but notice the signs. One particularly jarring moment was when a patient asked Allen to prescribe her Suboxone, while attempting to conceal the fact that she was 36 weeks pregnant. Suboxone is a drug used to reduce the symptoms of opiate addiction and withdrawal. But it can also be abused.

Needless to say, Allen knew that she’d have to supplement her education with more up-to-date training and expertise in addiction.

“Nobody taught me about [Suboxone] in school, and it’s been around for how long?” Allen said. “I’m an old-time doc in a new-time world. [We] do what we can to move them a little bit closer to [better] health. I think we can do that as long as we’re working together.”

After finishing his medical training at the Kirksville School of Osteopathic Medicine in Kirksville, Missouri, in 2008, Toney returned to Piedmont in 2011 to join his father’s practice, finding that times had changed in his hometown. Former classmates and others he had grown up with were struggling with opioids and other pills.

“People were [doing] what we call ‘doctor shopping’ — going to two or three doctors trying to get pain pills,” Toney said. “I didn’t understand it and then when I started looking, I found that opioid addiction is a chronic illness like anything else, and these people need help, not me saying, ‘Get out of here,’ which is the message they hear time and time again. So, when I started looking at that a different way, I can look back and think, ‘man, there [were] a lot of opportunities that I missed as well.’ ”

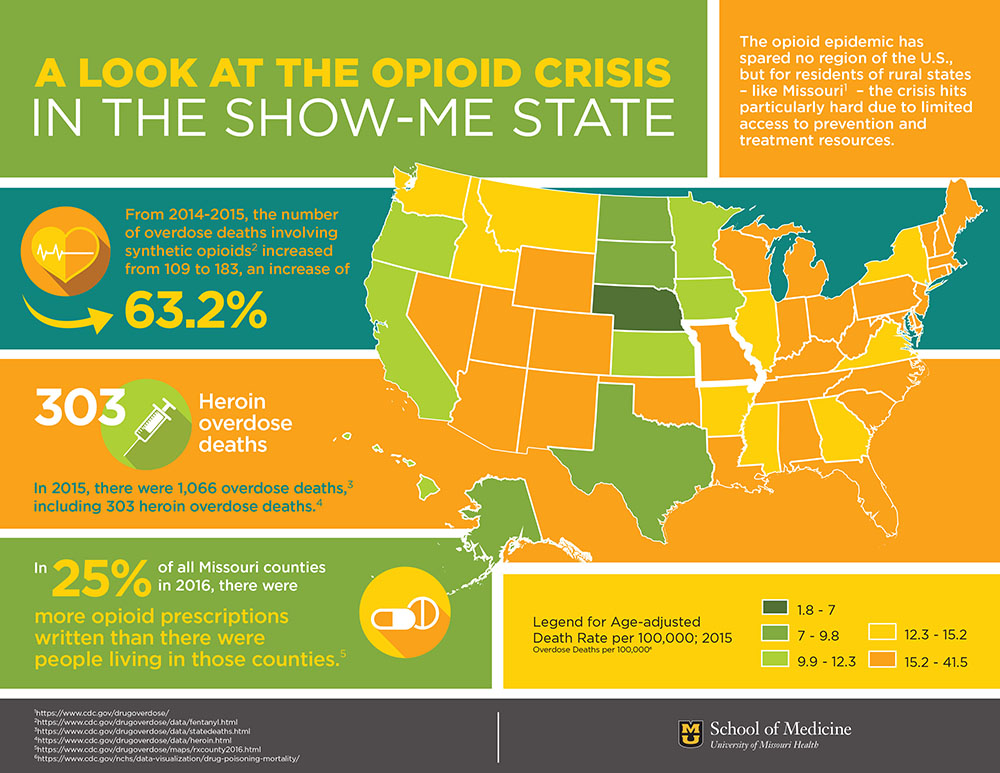

Doctors in places like rural Missouri have had no choice but to look at the opioid crisis differently, particularly over the past five years or so. In 2016, Missouri was ranked 14th in the United States for prescribing opioids, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Overdoses in Missouri from synthetic opioids – defined by the CDC as drugs like fentanyl and tramadol but excluding methadone – rose 63.2 percent from 2014 to 2015.

Statistics like this made opioid use an obvious pick for the University of Missouri School of Medicine’s next Show-Me ECHO. Asthma, autism, endocrinology, chronic pain management, dermatology, health care ethics and hepatitis C have been the subject of previous ECHOs. However, other telemedicine opioid use programs in New Mexico, New York, Massachusetts, Montana and other states made it clear to MU decision-makers that this was the right approach.

Rachel Mutrux, MU Health Care’s senior program director of telehealth, set a goal of 20 attendees for each Opioid Use Disorder ECHO; five sessions in, the average is 24. With funding from the State Targeted Response to the Opioid Crisis, this ECHO’s six-month curriculum set out to achieve three specific goals.

“The first one is to decrease opioid-related morbidity and mortality rates by using a medication-first strategy,” Mutrux said. “The second one is to teach evidence-based principles for harm reduction recovery and support strategies to supplement effective treatment. And the third one is to improve compassionate, patient-centered care for individuals with Opioid Use Disorder, and that is the heart of ECHO, right? It’s increasing the capacity of providers who can treat this specific disease.”

Allen presented a case of her own at an ECHO session. It featured the story of a woman who had been addicted to opioids for so long that she couldn’t “even get high anymore.” The goal for this patient, Allen said, was simply to “feel normal” again. Allen prescribed Suboxone, and early returns are good.

With the knowledge she’s gained through ECHO programming, Allen feels better equipped to combat the opioid crisis in Quincy and Hannibal. She’s hopeful that with this improved care, perceptions about addiction in her towns change for the better.

“It’s embarrassing to some of them to admit that,” Allen said. “They say, ‘I’m a drug addict.’ I say, ‘No, you have an opioid use disorder. You’re using your opioids inappropriately, but they are prescribed for you, and you’re using them for a different purpose than they were intended for.’ So, we can help … get to the root” of the problem.