As a nutritional biochemist, Elizabeth Parks, PhD, sees the effects of the obesity epidemic every day on a cellular level. In her lab, using pictures from a microscope, she looks at tissue samples and sees fatty livers. Parks refers to the liver as the body’s traffic cop, because it has to handle all the food we eat. When the liver is full of fat, it can be too sick to do its job, which leads to metabolic mayhem and an increased risk for diabetes.

Avoiding overeating is challenging because we don’t just eat for sustenance, we also eat for pleasure … and temptation is all around us. It lurks even in the checkout line at the hardware store, where a grinning clown on a plastic package beckons us to try his orange-colored, banana-flavored, legume-shaped marshmallow treats.

“Why do we need Circus Peanuts at the hardware store?” Parks said. “We don’t, but food is everywhere, and it’s highly processed and can taste really good. We need to stop blaming people for overeating and have some understanding of how difficult it is to stay weight stable in this environment. And we need to understand that our bodies handle food very differently. How I taste food and how you taste food might be completely different. Some people have a sweet tooth. Some don’t like bitter flavors or the tannins in red wine.”

When making dietary recommendations, a one-size-fits-all strategy does not work. Rather, people need to use tactics suited to their own genetics, environment, food preference and lifestyle.

That is precision nutrition, and that is the sweet spot of Parks’ research.

“We need the right treatment for the right person at the right time,” said Parks, who was elected to begin this fall as president of The Obesity Society, a scientific organization dedicated to the treatment of obesity. “We need to understand why some people have risks — not just genetically why they and their families struggle with weight, but how their genes affect the way they can be treated.”

Parks is known best in her field for her expertise in human fat metabolism. The liver converts sugars into fats, and in 2005 she made the discovery that this process causes fatty liver. That research explained why people who eat a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet could still have high levels of triglycerides in their blood. The study has been cited thousands of times in medical journals and changed the way clinicians understood and treated nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

“Elizabeth is one of the few scientists in the world who is able to track how and where the body metabolizes dietary fats and sugars using stable isotope tracers and mass spectrometry,” said R. Scott Rector, PhD, associate professor in the Department of Nutrition and Exercise Physiology and associate director of the NextGen Precision Health building. “She uses sophisticated techniques to understand how fats are created in the body and how their storage contributes to disease development and progression.”

Parks, Rector and hepatologist Jamal Ibdah, MD, have been collaborating with 11 other School of Medicine faculty colleagues on a five-year clinical study examining the effects of exercise and weight loss on liver health in people with NAFLD. Rector develops individualized high-intensity interval workouts that the participants perform three days a week. The team’s dietitian, Jen Anderson, creates personalized menus to help people in the study lose 8 to 10% of their body weight — which means at least 20 pounds — in nine months.

“For some people, that may mean they need to restrict sugar intake, and for others, it may mean restricting fat,” Parks said. “Jen tests a person’s response to food — playing off their metabolism to find the best diet for them. If you’re a patient of hers, she then focuses on your family situation, your work and the way you prefer to eat.”

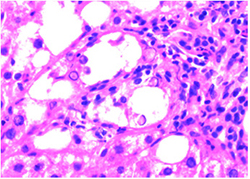

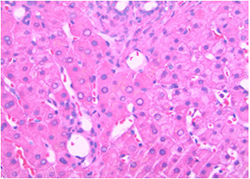

Personalizing the diet and workout plans requires more effort than treating everyone the same, but the payoff has been apparent, not only on the scales but also in the pictures under the microscope. When Parks looks at the before-and-after liver tissue samples of people who have completed the study, the white fat globules have disappeared, the liver is no longer inflamed and some subjects have less liver scarring. That suggests the liver, as the body’s traffic cop, is back on the beat and NAFLD is reversible if addressed early in the disease’s progression.

“With diet and exercise, we’re trying to hit the disease of NAFLD with as big a hammer as we possibly can,” Parks said. “The study of precision nutrition helps us understand how we can help people leverage taste preferences to make food choices that are more satisfying. The goal is to achieve lifelong healthy eating patterns.”