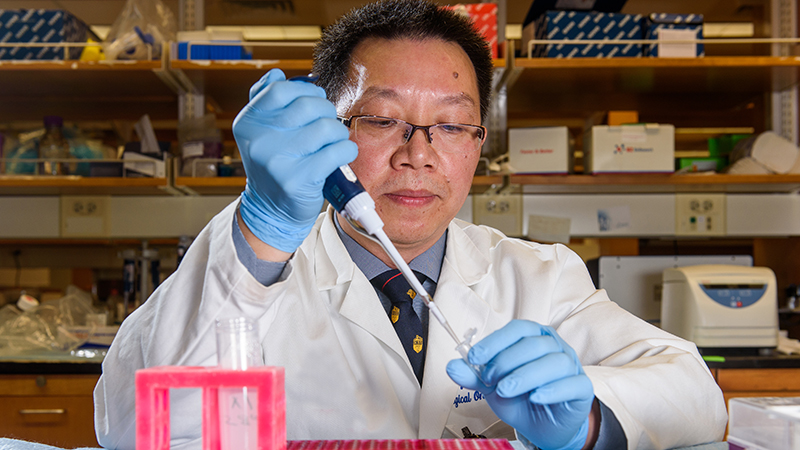

A conversation with Guangfu Li, PhD, DVM, on the topic of tumor immunology initially seems daunting. The research Li and his fellow investigators at the University of Missouri are conducting could lead to breakthroughs in the treatment of cancer, but it is high-level science that isn’t easily explained.

Within a few minutes, though, the barrier has been breached by sheer force of will. Li’s enthusiasm for his work is so overwhelming that a visitor must suppress the urge to find the nearest lab coat and beaker and get to work.

“He’s an amazing, amazing guy. He’ll never say no. It’s always time to work,” said Eric Kimchi, MD, one of Li’s long-time partners in research along with Kevin Staveley-O’Carroll, MD, PhD; Jussuf Kaifi, MD, PhD; and Diego Avella, MD.

Kimchi noted that Li and his crew of assistants are often in the lab when he leaves in the evening … and when he gets to work in the morning … and on weekends.

“Every day, I work very long, but I don’t feel tired, and it’s because of the environment that makes me feel very comfortable,” Li said.

If Li approaches his job with military discipline, it’s for good reason. After completing his master’s degree, he enlisted in the Chinese military to do research for a gene-engineering study. Li said he never did any fighting in his eight years of service — after three months of basic training, he began work at the Academy of Military Medical Sciences in Nanjing — but he was so successful in getting patents and publishing papers that he was promoted to a very high rank.

His reputation hasn’t diminished in his homeland after a decade in the United States.

“We went back to China last year in September. Really, they invited Dr. Li, and he brought all of us,” said Staveley-O’Carroll, the former surgery chair of the MU School of Medicine and former director of Ellis Fischel Cancer Center. “He throws lightning bolts in China. He is well-regarded.”

Li came to America to do post-doctoral work at Penn State studying immune responses to malaria. He planned to stay no more than two years. However, his son, who was in middle school at the time, wanted to stay.

So the family stayed.

By that time, Li had connected with Staveley-O’Carroll, who was championing the use of immunotherapy in treating cancer.

“Dr. Staveley-O’Carroll said this is a promising strategy, because even if we don’t find the very typical markers for the cancer, after the cancer grows, it induces immunotolerance. That’s why cancer cannot be rejected. Is it possible if we reactivated the immune system, it probably could kill tumor cells?

“At that time, there were a lot of questions there, but I totally agreed with Dr. Staveley-O’Carroll’s opinion about cancer immunotherapy. I thought, ‘This a very promising project. I’m really, really, very interested in this project.’ ”

The same team that started together at Penn State is now at MU, with a stop along the way at the Medical University of South Carolina. The group has stuck together because of passion for its research, as well as close friendships among the members.

The significance of their work has led to multiple active R01 grants from the National Institutes of Health worth a combined $4.3 million. All are related to liver cancer and the possible use of immunotherapy to fight the disease.

The team has developed a mouse model that mimics a human with liver cancer. Hepatocellular cancer — in which tumors originate in the liver — is usually diagnosed in patients with badly damaged livers. The organ is often so scarred that it could not regenerate if a tumor were removed, thus surgery is not an option.

The only treatment for the disease is the chemotherapy drug sorafenib, which increases life expectancy by a few months. Sorafenib suppresses the immune system, so it isn’t a good choice to pair with immunotherapy. There is a similar chemo drug called sunitinib that is not FDA-approved for liver cancer treatment because trials showed it had similar effectiveness but more side effects. However, the MU researchers believe sunitinib can alert the immune system that it needs to attack the tumor and thus could pair well with immunotherapy. One of the R01 grants is devoted to research whose goal is showing the ways sunitinib switches on the immune system.

Another R01 grant — issued in July and worth more than $2.7 million — deals with the use of a compound developed by former colleague Mark Kester of the University of Virginia called nanoliposome-loaded C6-ceramide (LipC6) in combination with immunotherapy. The purpose of the study is to determine how LipC6 breaks tumor-induced immune tolerance and to develop a LipC6-integrated immunotherapy for clinical use. Staveley-O’Carroll, Li and Kester are the principal investigators on that project.

While everyone contributes to the research, the time of Staveley-O’Carroll, Kimchi, Kaifi and Avella is devoted heavily to clinical and surgical duties, so much of the day-to-day lab work falls to Li and his assistants.

His efforts are appreciated by his team members now and perhaps valued by cancer patients later.

“When I see Dr. Li in the hallway,” Kimchi said, “I always give him a hug.”