The formula for a person developing cardiovascular disease is often heredity plus vices plus time. Family history of the disease, diabetes, smoking and a high-fat diet are among the top risk factors.

But sometimes the culprit isn’t one of the usual suspects.

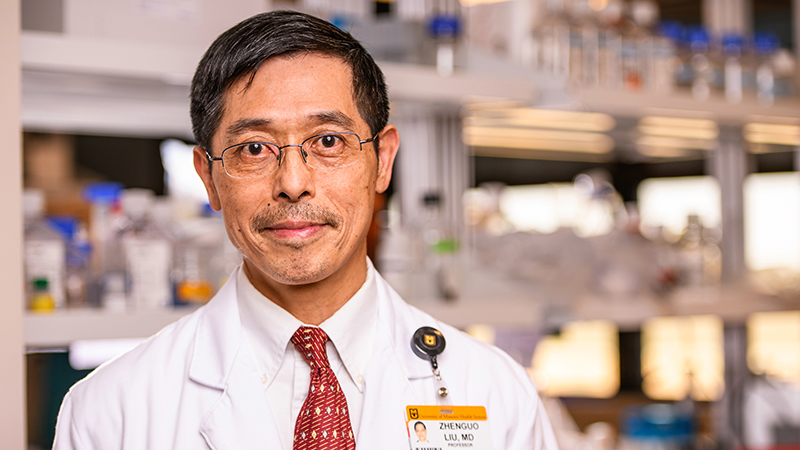

Zhenguo Liu, MD, PhD, wondered why some young people develop atherosclerosis — plaque buildup in an artery that can lead to a heart attack or stroke — without any of the typical risk factors.

“We know lipids, diabetes and smoking are not good things, but even when we control those conditions, people still develop atherosclerosis,” said Liu, former director of the MU School of Medicine’s Division of Cardiovascular Medicine and a former cardiologist at MU Health Care. “Especially the young patients, you do not expect them to have this condition. Why do they develop it?”

Using precision medicine to dive into each patient’s unique bacteria makeup, Liu and his team are establishing a link between a stomach bacteria and atherosclerosis. An estimated 30 to 50% of people in developed countries and up to 80% of people in undeveloped countries have the Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) bacteria in their gut, although most don’t realize they have it. The most likely cause is contaminated drinking water.

The bacteria can be detected through a breath test and in most cases killed with antibiotics. Liu’s goal is to prove the connection between the bacteria infection and atherosclerosis, so he can establish regular bacteria screenings for young people. That would allow doctors to identify which patients are at the most risk for cardiovascular disease and proactively treat them.

“This may not be the key risk factor for the advanced stage of the disease, but it is an additional risk factor that’s easily identifiable and treatable,” Liu said. “If you’re able to prevent this one early on, you’re much better off later in life when other risk factors for atherosclerosis kick in.”

Liu partnered with doctors in his native China in a recent study published in the journal Atherosclerosis. More than 17,000 Chinese people were screened for H. pylori and given an ultrasound to detect atherosclerosis in their carotid arteries — the major vessels in the neck that supply blood to the brain. The researchers found that in males under the age of 50, those infected with H. pylori were more likely to have atherosclerosis than those who weren’t infected. Liu said it’s unclear why the bacteria isn’t a risk factor for atherosclerosis in females.

“Patients and animals infected with this bacteria develop dysfunction of endothelial cells in the arteries,” Liu said. “It plays a critical role for the function of the vessel. If we get rid of this bacteria, the vascular function is able to recover.”

In September 2019, Liu received a four-year grant from the National Institutes of Health to determine whether mice could develop atherosclerosis easier after being infected with H. pylori bacteria. When the COVID-19 situation is under control, Liu is planning to start a small clinical study of 80 volunteers aged 18-35. His team will screen the volunteers for the bacteria and then use ultrasound imaging to test them for vascular function. Those with H. pylori infection will be treated with antibiotics and receive a follow-up ultrasound to see if their vascular function improves after the bacteria is eradicated.

“This is a significant public health issue that can be helped with precision medicine,” Liu said. “The goal is to change the practice of preventing cardiovascular disease by screening the young population every three or five years to see if the individual is infected with this bacteria. If they are, we can treat accordingly.”