In 1990, the University of Missouri School of Medicine had just received a backhanded compliment from the LCME. The medical school accreditation agency noted that MU had a “perfectly preserved 1960s curriculum.”

At the time, the curriculum included a two-year component of basic science, in which students learned mostly through lectures and memorization, and a two-year component of clinical practice.

Lester Bryant, the MU School of Medicine dean, scheduled a breakfast meeting with Michael Hosokawa, EdD, then a professor of family medicine and now the senior associate dean of education. Bryant put Hosokawa in charge of finding a better way to train the next generation of doctors.

“Information we give students has an estimated half-life of about four to six years,” Hosokawa said. “In other words, when our students graduate, about half of what we taught them is out of date, because science is changing so rapidly. We decided we had to teach students to live in a world we couldn’t even imagine. That meant we had to look at problem-solving rather than large amounts of information.”

Hosokawa and the members of the curriculum design committee became intrigued with problem-based learning — a practice that had spread from its Canadian birthplace of McMaster University to a handful of American colleges — as the best way to teach first- and second-year medical students.

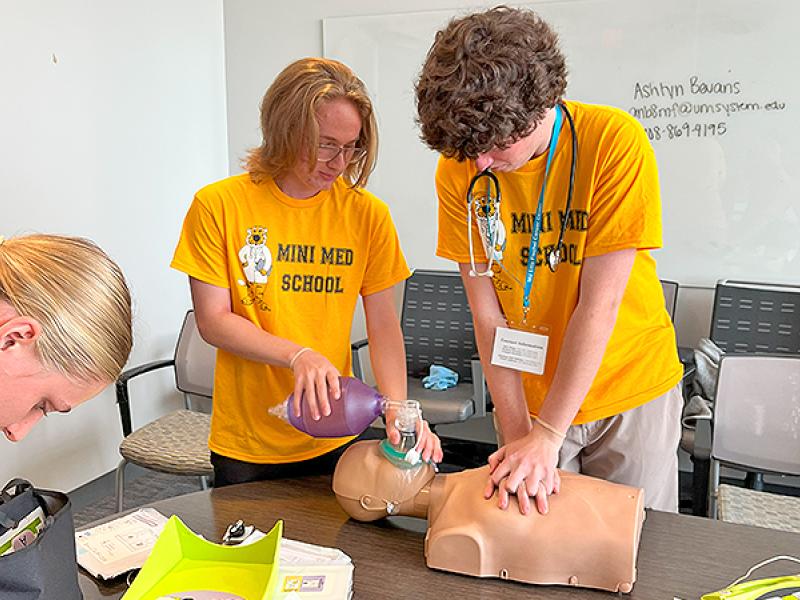

In PBL, students work in teams of eight to learn from real clinical cases. They teach each other by researching and reporting back on topics related to that week’s case. The teacher in the room is referred to as a faculty facilitator, and his or her role is to keep the students on the right track and provide guidance.

Hosokawa and his team had two big jobs: 1, design the new curriculum; 2, convince the faculty the new curriculum would not ruin the University of Missouri School of Medicine.

With the strong backing of Bryant, Hosokawa divided and conquered. He called the people who planned the system “innovators.” They helped spread the gospel to the “early adopters,” who were eager to try something new, and then the “early majority,” who were at least willing to give it a fair shot. The stragglers, he hoped, would fall in line once the success of the new system was obvious.

The new curriculum launched in the fall of 1993.

“People would jokingly say we were guinea pigs, but I don’t think too many students really thought that way,” said MU associate dean for student programs Laine Young-Walker, MD, who was a student in the inaugural class. “I can’t speak for everybody, but I know for me and the people in my circle, nobody thought, ‘This is bad, and I’m not going to stay here.’”

Although the new way of learning seemed to be working, PBL’s proponents worried for two years about the results of the United States Medical Licensing Examination Step 1 test, which measures the science knowledge of students at the end of their second year of medical school. Hosokawa needed an early win.

“If this failed, I was probably going to become a high school science teacher,” he said.

Hosokawa recalled a nervous group of administrators gathering for the opening of the envelope. It revealed Step 1 scores that were a bit below the national average but were better than the previous year. That was a relief. The next year, MU’s Step 1 scores exceeded the national average, and they have remained above average ever since.

MU has become a model program for universities from as far away as Taiwan, where all 12 medical schools use a version of Missouri PBL.

Along the way, MU adjusted the curriculum’s name from problem-based learning to patient-based learning. Not much else has changed.

Now, Hosokawa and his colleagues are thinking about the future, lest MU be accused of using a perfectly preserved 1990s curriculum.

“We want to begin a process to update our curriculum, if not join some other schools to look at the next major change in medical education,” Hosokawa said. “It might involve PBL, because PBL has been so successful, but it might be totally different. Again, we need to prepare our students to practice in a world we can’t imagine.”