A diet high in protein is often promoted as part of a healthy lifestyle. Many diets encourage consumers to reduce carbohydrates and fats in favor of protein to lose weight and gain lean muscle. However, researchers from the University of Missouri School of Medicine have uncovered how consuming dietary protein in excess of the recommended daily allowance triggers signals at the cellular level that result in adverse cardiovascular and metabolic health effects.

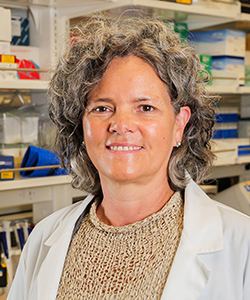

Bettina Mittendorfer, PhD, senior associate dean for research at the University of Missouri School of Medicine and director of the NextGen Precision Health Clinical and Translational Science Unit led a research team at the Roy Blunt NextGen Precision Health building. They found that while the prevailing advice for promoting good health is that increasing the proportion of protein in daily calorie intake is beneficial, consuming protein in excess not only doesn’t add to the development of lean muscle but can cause unintended adverse health effects.

“Consumers are being led to believe that they can never get too much protein in their diet, with a variety of foods and even beverages enriched with protein and promoted as a way to increase the proportion of protein in their diet,” said Mittendorfer. “However, our research shows that specific amino acids, which are the building blocks of protein, can trigger cardiovascular disease through a signaling mechanism at the cellular level in the blood.”

An amino acid found in animal-protein foods, such as beef, eggs and milk, was found to be responsible for signaling activity in macrophage cells that typically clear away debris in blood vessels. As consumption of dietary protein increases, so does the consumption of leucine, the specific amino acid responsible for triggering this macrophage cellular activity in the blood. When functioning normally these macrophage cells work to keep blood vessels free from plaque buildup. When their production becomes overactive the resulting accumulation of spent cells in the vascular system can cause the plaque buildup and blockages they are supposed to prevent. The resulting atherosclerosis, or hardening of the arteries, is a leading risk factor for heart attack and stroke.

“Not getting enough dietary protein is bad for health, but too much might also carry adverse health effects due to this macrophage signaling mechanism,” said Mittendorfer. “Our hope is to eventually find the goldilocks approach for maximizing the health benefits of dietary protein, such as building lean muscle, while avoiding the health drawbacks from overconsumption.”

The researchers found that consuming more than 22 percent of daily calories from protein carries more downside risk than dietary benefit. For a normal adult, 20 to 30 grams of protein per meal, or 60 to 90 grams of protein per day is adequate to support health.

The study, which combined small human trials with experiments in mice and cells was done in collaboration with researchers from the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Washington University of St. Louis School of Medicine, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center and the University of Toronto.

Additional clinical trials to evaluate the effects of different amounts and types of dietary proteins on the signaling pathways identified are needed to ensure current dietary guidelines concerning protein intake are appropriate or revised accordingly.

“Identification of a leucine-mediated threshold effect governing macrophage mTOR signaling and cardiovascular risk” was recently published in Nature Metabolism. In addition to Mittendorfer, the research team from the University of Missouri School of Medicine included scientist Alan Fappi, PhD; and postdoctoral fellow Vasavi Shabrish, PhD.. The research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the American Diabetes Association and the Longer Life Foundation.

Highlighting the promise of personalized health care and the impact of large-scale interdisciplinary collaboration, the NextGen Precision Health initiative is bringing together innovators from across the University of Missouri and the UM System’s three other research universities in pursuit of life-changing precision health advancements. It’s a collaborative effort to leverage the research strengths of Mizzou toward a better future for the health of Missourians and beyond. The Roy Blunt NextGen Precision Health building at MU anchors the overall initiative and expands collaboration between researchers, clinicians and industry partners in the state-of-the-art research facility.