Dear Colleagues,

Last week, we had a viewing of the documentary called “Black Men in White Coats” at the MU School of Medicine followed by a panel discussion. The documentary pointed out that fewer and fewer Black men are entering into medicine. I would like to share about one inspiring physician who epitomizes the need for more Black men in white coats, Louis Tompkins Wright, MD.

Dr. Wright was part of a family of physicians going back to the 1800s. He attended Clark University and Harvard Medical School, where he experienced discrimination on many fronts as a Black student. He initially was told he could not deliver babies at one of the Boston hospitals, but he objected and persevered. Prior to that, Black students were only allowed to deliver Black babies. His stance abolished this practice.

Despite graduating with honors, because he was Black, he could not get an internship at Massachusetts General Hospital or Peter Bent Brigham Hospital. He did his internship at Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington, D.C., a hospital for Blacks. He practiced briefly in Atlanta before entering the U.S. Army as a doctor in WWI. During this time, he introduced the intradermal method of vaccination for smallpox, which was adopted by the U.S. Army Medical Corps. Later, he was placed in charge of a military hospital in France, the youngest surgeon to hold such a position. He was awarded the Purple Heart, remained in the Reserves and rose to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel.

After the war, he began a surgical practice in New York City and became the first Black physician appointed to the staff of Harlem Hospital or any New York City hospital. Four white doctors resigned in protest. Twenty-three years later, he became director of surgery and ultimately became the president of the medical board. Dr. Wright specialized in head injuries and fractures and invented several braces and surgical devices.

His accomplishments in surgery led him to become the first Black physician admitted to the American College of Surgeons. He excelled not only in surgery but became an expert in the use of antibiotics such as Aureomycin and Terramycin for infections. A man of many talents, he also became a leader in cancer therapy and founded the Harlem Hospital Cancer Research Foundation where early chemotherapeutic research trials were performed.

Dr. Wright was an outspoken and forceful fighter for equal rights for Blacks and led efforts to stop segregated hospitals which he maintained “represent a duality of citizenship in a democratic government that is wrong.” In 1952, Dr. Wright received a citation from the John A. Andrews Memorial Hospital of the Tuskegee Institute for his contributions to interracial health programs in the North and South. He was cited for his “distinguished services in the cause of humanity, for resolute leadership of allied humanitarian and civic organizations dedicated to the advancement of social, economic and related conditions basic to the health of all the people.”

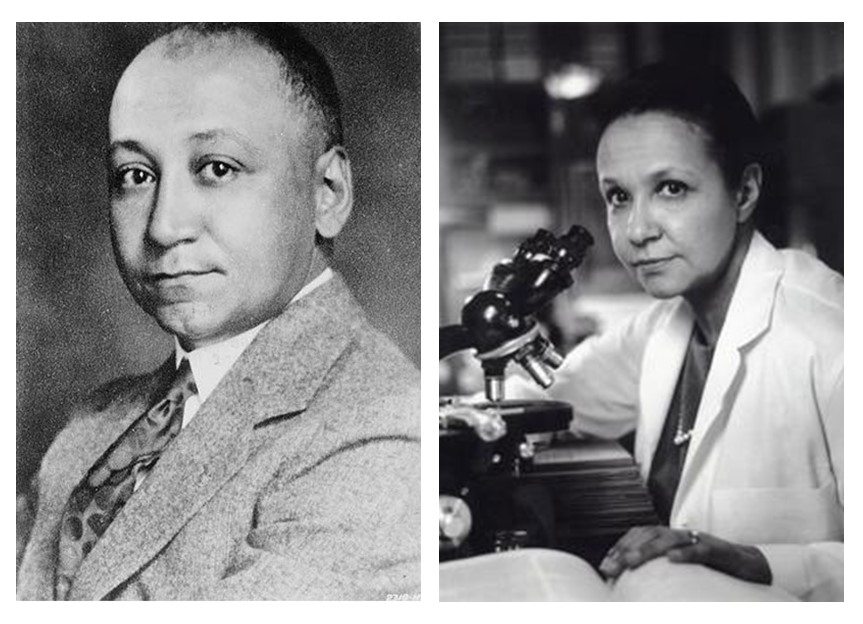

As we think about Black History Month, please honor and appreciate some of the giants like Dr. Louis Tompkins Wright. The world needs many more Black men in white coats such as him — and Black women in white coats like his daughter, Dr. Jane Wright.

Sincerely,

Richard Barohn, MD

Executive Vice Chancellor for Health Affairs

University of Missouri

rbarohn@health.missouri.edu

1: Louis Tompkins Wright papers, 1879, 1898, 1909-1997. H MS c56. Harvard Medical Library, Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, Boston, Mass.