Diana Gil Pagés, PhD, has made T cells her life’s work. Her study of the tiny soldiers of the immune system shaped the course of her professional life, leading her from Spain to Missouri, where she is developing a treatment that would alert T cells to attack the cancers they’ve been tricked into ignoring.

But that’s only half of the story. Her marriage, friendships and even the name of the just-for-fun rock band that occasionally gets together to jam after a long day in the lab — all of it is bonded by T cells.

Although Gil Pagés couldn’t have predicted all those details, it was clear from an early age that science would shape her life. While growing up in Madrid, her favorite TV shows were documentaries featuring Spanish naturalist Félix Rodríguez de la Fuente, French oceanographer Jacques Cousteau and American astronomer Carl Sagan. Her father, whose formal schooling ended at age 13, read biochemistry textbooks for pleasure, and he passed along those books and his appetite for knowledge to his daughter.

“When I was a teenager, I was already thinking about cancer and about making my own little contribution,” Gil Pagés said.

As it turned out, her contribution is not so little. In 2019, she was awarded a $3.7 million grant as part of the National Cancer Institute’s Moonshot Initiative to explore an immunotherapy that could change lives.

“By the end of my PhD, I was already working on the things that have now allowed me to develop this new therapy,” said Gil Pagés, who holds a dual appointment as an associate professor of surgery at the MU School of Medicine and associate professor of bioengineering at the MU College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources. “I just didn’t know then that I was going to make a therapy out of it.”

Love at first science

Adam Schrum was pursuing a PhD in immunology at the University of Pennsylvania in 2002 when he read a paper in the scientific journal Cell by a Spanish doctoral student. He was enthralled by her discovery about the actions of a particular T cell receptor — CD3 — and what it might mean for the future of immunotherapy.

“I personally printed out copies of that paper for every person in the lab and placed it on their desks,” Schrum said. “I never did that in any other case. I was blown away by this paper.”

About six months later, Schrum was interviewing for a position as a postdoctoral fellow in the laboratory of international immunology expert Ed Palmer at the University of Basel in Switzerland. Palmer introduced him to a postdoc who had just arrived from Madrid. Her name was Diana Gil Pagés.

Schrum began gushing about her breakthrough paper. When that had little effect, he brought up a lesser-known paper she had published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry. A surprised Gil Pagés told him that nobody knew about that paper.

“Well,” he responded, “I do.”

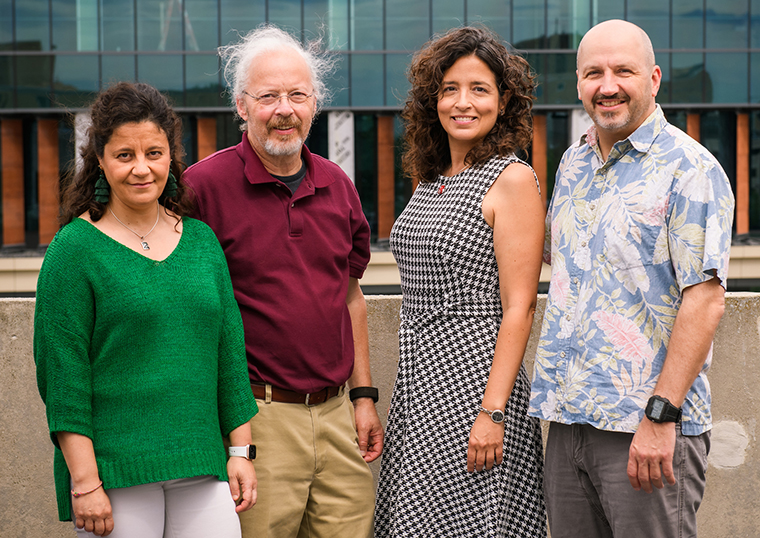

Gil Pagés and Schrum soon became a couple. So did another Spanish woman/American man pair of postdocs — Emma Teixeiro Pernas and Mark Daniels. They formed an inseparable four-person team, doing experiments by day, exploring Basel at night and taking train trips to Germany, France and Italy on the weekends.

Health building.

They even formed a band, CARMA and the T’s, named for the CARMA protein Teixeiro Pernas was studying and the T cells they were all trying to understand. Teixeiro Pernas sang, Daniels played drums and Schrum handled the guitar. Gil Pagés had no musical training, but she did her best on the bass. The group, which played rock ’n’ roll cover songs, practiced in an empty lab and played live at the institute’s holiday party.

They had a blast for the four years of the fellowship, and then it was time for them to start their own labs. Marriage wasn’t far off for both couples. Teixeiro Pernas and Daniels went to the University of Missouri. Gil Pagés and Schrum went to the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

“In Rochester, I had my first ideas about manipulating the T cells to create a therapy,” Gil Pagés said. “It was there that I got the first evidence that it may be a possibility.”

A Fab idea

Our immune system constantly identifies and destroys foreign invaders. Sometimes cancer cells beat the system, fooling the T cells into leaving them alone, which allows the disease to grow and spread. The field of tumor immunology is devoted to helping the T cells recognize the threat and respond.

The most common form of immunotherapy is checkpoint inhibition, in which drugs block a specific protein whose job is to put the brakes on the immune response. With no brakes, the T cells are free to attack the cancer cells.

Gil Pagés developed a different approach to immunotherapy by altering the T cells themselves to make them more alert to danger. She injects antigen-binding fragments — also known as Fab fragments — which attach to the T cells’ receptors. The Fab fragments cause the receptors to change shape and signal a strong immune response to previously undetected cancer cells.

In experiments on mice with metastatic melanoma, the treatment causes the tumors to grow far slower than they do in untreated mice. When the Fab fragment therapy is used in conjunction with other treatments, the tumors grow even slower. Gil Pagés said that in principle the Fab fragment treatment also could apply to other cancer types. So far, she hasn’t found any side effects.

“You would expect it to cause autoimmune attacks, but we haven’t seen them,” Gil Pagés said. “We don’t fully understand that. It’s possible that our tweaking of the T cells is very subtle. We may just help a little bit but not enough to cause autoimmune diseases.”

The band gets back together

During their 10 years at the Mayo Clinic, Gil Pagés and Schrum stayed in touch with their friends in Missouri. In 2018, they were recruited to MU through a “Biomedical Innovations collaboration that included the Department of Surgery; the Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology; and the Department of Biomedical, Biological and Chemical Engineering.

“Mizzou offered us a great opportunity, and there was already the attraction of Mark and Emma,” Gil Pagés said. “We haven’t regretted it — not once. It’s been really good for us here with the students, the postdocs and our friends.”

Gil Pagés and Schrum share a lab, and their offices are next door to each other. They get the chance to collaborate professionally — and musically — with Teixeiro Pernas and Daniels again.

“We reunited the band,” Texeiro Pernas said. “We get together from time to time, even though we are busy with young families.”

For Gil Pagés, the move to Missouri has given her the chance to take the next step in a career spent honing the brilliant discovery she made in graduate school. She is eager to test the Fab fragment treatment on human T cells in a clinical trial.

“I’ve added some ideas created by the new environment and the collaborators that are around here to explore in more realistic ways how this may work for humans,” Gil Pagés said. “For mice, we have a proof of concept that it may work. Now, the question is: Can we translate it into humans?”

Article Spotlight

The precision medicine research conducted at the MU School of Medicine is part of NextGen Precision Health, an initiative to expand collaboration in personalized health care and the translation of interdisciplinary research for the benefit of society. The Roy Blunt NextGen Precision Health building at Mizzou anchors this statewide initiative, which aims to unite government and industry leaders with innovators from across the system’s four research universities in pursuit of life-changing precision health advancements. The University of Missouri System’s bold NextGen initiative highlights the promise of personalized health care and the impact of large-scale interdisciplinary collaboration.